|

"Silas Marner

was both sane and honest, and as with many

honest and fervent men,

culture had not defined any channels

for his sense of mystery, and so it

spread itself over the proper

pathway of inquiry and knowledge.

He had inherited from his mother

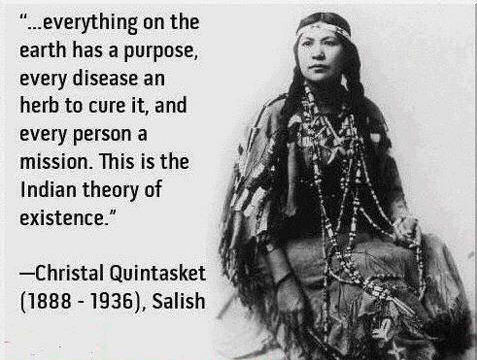

some acquaintance with medicinal

herbs and their preparation, a little store of wisdom which she had

imparted to him as a solemn bequest but of late years he had had

doubts about the

lawfulness of applying this knowledge, believing that herbs could have no

efficacy without prayer, and that prayer might suffice without herbs; so that

the inherited delight he had in

wandering in the fields in search of foxglove and dandelion and coltsfoot,

became to him the

character of temptation.

Among the members of his church there was

one young man, a little older than himself, with

whom he had long lived in

such close friendship that it was the

tradition of Lantern

Yard brethren to call them David and Jonathan.

The real name of the

friend was William Dane, and he, too, was regarded as a shining instance of

youthful piety, though somewhat

given to over severity towards weaker brethren, and

to be so dazzled by his own light as

to hold himself wiser than his teachers.

Whatever blemishes others

might discern in William, to his friend he was faultless; Silas Marner an

impressible self doubting

nature which, at an inexperienced age, admire imperativeness and

leans on

contradiction.

The

expression of trusting

simplicity in Silas Marner's face, heightened by that absence of

special observation,

that defenseless, deer like gaze which belongs

to large prominent eyes, was strongly contrasted by

the self complacent suppression

of inward triumph that lurked in the narrow slanting eyes and compressed lips

of William Dane.

One of the most frequent topics of conversation

between the two friends was assurance of salvation:

Silas Marner confessed that he could never arrive at anything higher than

hope mingled with

fear, and

listened with longing

wonder when William

declared that he had possessed unshaken assurance ever since, in

the period of his

conversion, he had dreamed that

he saw the words 'calling and

election sure' standing by themselves on a white page in the open Bible.

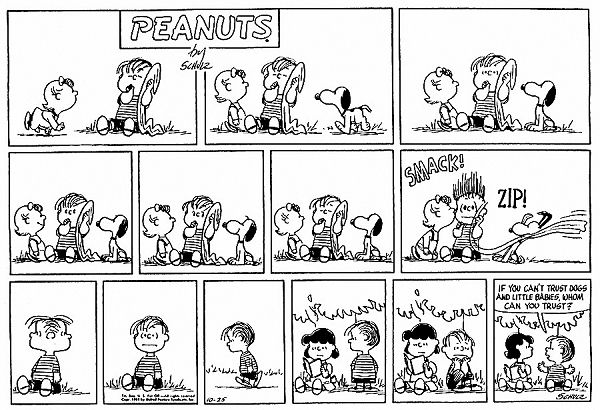

Such colloquies have entranced many

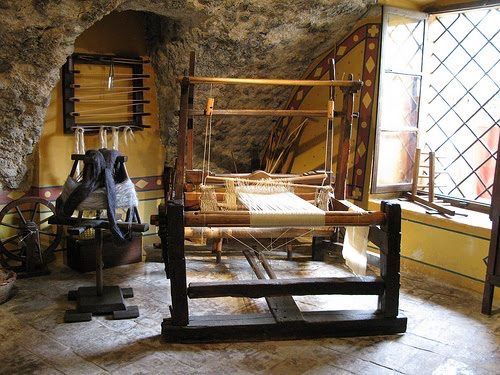

pale faced weavers, whose

unnurtured souls have been

like young winged things, fluttering forsaken in the

twilight.

It had seemed to the naive Silas

Marner that the friendship had

suffered no chill even from his formation of another

attachment of a closer category.

For

some months he had been engaged to

a young servant woman,

waiting only for a little increase to their mutual savings in order to marry;

and it was a great delight to him that Sarah did not object to William's

occasional presence in their Sunday interviews.

It was at this point in

their history that Silas Marner's cataleptic fit occurred during the prayer

meeting; and amidst the various queries and expressions of interest addressed

to him by his fellow members, William's suggestion alone

jarred with the general

sympathy towards a brother thus singled out for special dealings.

He

observed that, to him, this

hypnotic trance

looked more like a visitation of

Satan than a proof of

divine favor, and exhorted his

friend to see that he hid no accursed thing within his soul.

Silas

Marner, feeling bound to accept rebuke and admonition as a brotherly office,

felt no resentment, but

only pain, at his friend's doubts concerning

him; and to this was soon added some

anxiety at the perception

that Sarah's manner towards him began to exhibit a strange fluctuation between

an effort at an increased

manifestation of regard and

involuntary signs of

shrinking.

He asked her if she wished to break off their engagement;

but she denied this: their engagement was known to the church, and had been

recognized in the prayer meetings; it could not be broken off without strict

investigation, and Sarah could render no reason that would be

sanctioned by the feeling of

the community.

At this time the senior deacon was taken dangerously

ill, and, being a childless widower, he was tended

night and day by some of the younger

brethren or sisters.

Silas Marner frequently took his turn in the night

- watching with William, the one relieving the other at two in the morning.

The old man, contrary to expectation,

seemed to be on the way to recovery, when one night Silas Marner,

sitting up by his

bedside, observed that his usually audible breathing had ceased.

The candle, burning low, had

to lifted to see the patient's face distinctly.

Examination

convinced him that the deacon was dead - had been dead some time, for the limbs

were rigid.

Silas Marner asked himself if he had been asleep, and

looked at the clock: it was already four in the morning.

How was it

that William had not come?

In much anxiety he went to seek help, and

soon there were several friends assembled in the house, the minister among

them, while Silas Marner went away to his work, wishing he could have met

William to know the reason of his non-appearance.

At six o'clock, as he

was thinking of going to seek his friend, William came, and with him the

minister.

They came to summon him to Lantern Yard, to meet the church

members there; and to his inquiry concerning the cause of the summons the only

reply was, 'You will hear.'

No thing further was said until Silas

Marner was seated in the vestry, in front of the minister, with the eyes of

those who to him represented God's people fixed solemnly upon him.

The minister, taking out a pocket-knife, showed it to Silas Marner,

and asked him if he knew where he had left that knife?

Silas Marner

said, he did not know that he had left it anywhere out of his own pocket - but

he was trembling at this strange interrogation.

He was then exhorted

not to hide his sin, but to confess and repent.

The knife had been

found in the bureau by the departed deacon's bedside - found in the place where

the little bag of church money had lain, which the minister himself had seen

the day before.

Some hand had removed that bag; and whose hand could it

be, if not that of the man to whom the knife belonged?

For some time

Silas Marner was mute with astonishment:

then he said, God will

clear me: I know nothing about the knife being there, or the money being gone.

Search me and my dwelling: you will find nothing but three pound five of my own

savings, which William Dane knows I have had these six months.'

At this

William groaned, but the minister said, 'The proof is heavy against you,

brother Silas Marner. The money was taken in the night last past, and no man

was with our departed brother but you, for William Dane declares to us that he

was hindered by sudden

sickness from going to take his place as usual, and you yourself said that

he had not come; and, moreover, you neglected the dead body.'

'I must

have slept,' said Silas Marner. Then, after a pause, he added, 'Or I must have

had another visitation like that which you have all seen me under, so that the

thief must have come and gone while I was not

in the body, but out of the body. But, I say again, search me and my dwelling,

for I have been nowhere else'.

The search was made, and it ended - in

William Dane's finding the well known bag, empty, tucked behind the chest of

drawers in Silas Marner's chamber!

On this William

exhorted his friend to

confess, and not to hide his sin any longer.

Silas Marner turned a

look of keen reproach on him, and said, 'William, for nine years that we have

known each other, have you ever known me tell a lie?

But God will clear

me.'

'Brother,' said William, 'how do

I know what you may have done in

the secret chambers of your

heart, to give Satan an advantage over you?'

Silas Marner was still

looking at his friend. Suddenly a deep flush came over his face, and he was

about to speak impetuously, when

he seemed checked again by some

inward shock, that sent the flush back and made him tremble.

But at

last he spoke feebly, looking at William. 'I remember now - the

knife wasn't in my pocket.'

William said, 'I know nothing of what you

mean.'

The others present, however, began to inquire where Silas Marner

meant to say that the knife was, but he would give no further explanation: he

only said, 'I am

sore stricken; I can say nothing.

God will clear me.'

On their return to the vestry there was further deliberation. Any

resort to legal measures for ascertaining the culprit was contrary to the

principles of the Church: prosecution was held by them to be forbidden to

Christians, even if it had been a case in which there was no scandal to the

community.

But they were bound to take other measures for finding out

the truth, and they resolved on praying and drawing lots.

This resolution can be a

surprise to those who are unacquainted with that obscure relgious life

which has gone on in the alleys of our towns.

Silas Marner knelt with his

brethren, relying on his own

innocence being certified by immediate divine intervention,

feeling sorrow, for

his trust in man had been cruelly

bruised.

The lots declared that Silas Marner was guilty.

He

was solemnly suspended from church membership, and called upon to render up the

stolen money: only on confession, as the sign of repentance, could he be

received once more within the fold of the church.

Silas Marner

listened in

silence.

At last, when every one rose to depart, he went towards

William Dane and said, in a voice

shaken by agitation - 'The last time I remember using my knife, was when I

took it out to cut a strap for you. I don't remember putting it in my pocket

again. You stole the money, and you have

woven a plot to lay the sin at my

door. If you prosper there is no just God that

governs the earth righteously, but a God of

lies, that bears witness against the innocent.'

There was a general shudder at

this blasphemy.

William said meekly, 'I leave our brethren to judge

whether this is the voice of Satan or not.

I can do nothing but pray for

you, Silas Marner.'

Poor Silas Marner went out with that despair in

his soul - that shaken

trust in God and man, which is little short of madness to a loving nature.

In the bitterness of his wounded spirit, he said to himself, 'She will

cast me off too.'

And he reflected that, if she did not believe the

testimony against him, her whole faith must be upset, as his was.

To

humans accustomed to reason about the forms in which their relgious feeling has

incorporated itself, it is difficult

to enter into that simple, untaught

state of mind in which the

form and the feeling have never been severed by

an act of reflection.

We are apt to think it inevitable that a man in Silas Marner's position

should have begun to question the validity of an appeal to the divine judgement

by drawing lots; to him this would have been

an effort of independent thought

such as he had never known; and he must have made the effort at a moment

when all his energies were turned into

the anguish of disappointed

faith.

An angel who records the sorrows of men as well as their sins

knows many and deep are

sorrows that spring from false ideas for which no man is culpable.

Silas Marner went home, and for

a whole day sat alone, stunned

by despair, without any impulse to go to Sarah and

attempt to win her belief in his innocence.

The second day he took refuge from benumbing unbelief, by

getting on his loom and working away as usual;

and before many hours were past, the minister and one of the deacons came to

him with the message from Sarah, that she held her engagement to him at an end.

Silas Marner received the message

mutely, and then turned away from the messengers to work at his loom again.

In little more than a month from that time, Sarah was married to

William Dane; and not long afterwards it was known to the brethren in Lantern

Yard that Silas Marner had departed from the

village.

"Year after year, Silas Marner

had lived in solitude,

his guineas rising in the iron

pot, his life narrowing and hardening itself more and more into a mere

pulsation of desire and satisfaction that had no relation to any other being.

His life had

reduced itself to the mere functions of weaving and hoarding, without any

contemplation of an end towards which the functions tended.

The

same sort of process has perhaps been under gone by wiser men, when they have

been cut off from faith and

love only, instead of a loom and a heap of

guineas, they have had some

erudite research, some ingenious

project, or some

well-knit theory.

'Where is the money?' now

took such entire possession of

Dunstan as to make him quite

forget that the weaver's death was not a certainty.

A dull mind, once arriving at

an inference that flatters

an unnatural desire, is rarely able to

retain the impression that the notion

from which the inference started was problematic.

And Dunstan's

mind was as dull as the mind of a

psychopath usually is.

There were only three hiding places where he

had ever heard of cottagers' hoards being found: the thatch, the bed, and a

hole in the floor.

Silas Marner's

cottage had no thatch; and Dunstan's first act,

after a train of thought made rapid by the stimulus of cupidity, was to go up

to the bed; but while he did so, his eyes traveled eagerly over the floor,

where the bricks, distinct in the

fire light, were discernible under the sprinkling

of sand.

But not everywhere; for there was one spot, and one only,

which was quite covered with sand, and sand showing the marks of fingers which

had apparently been careful to spread it over a given space.

It was near

the treddles of the loom.

In an instant Dunstan darted to that spot,

swept away the sand with his whip, and, inserting the thin end of the hook

between the bricks, found that they were loose.

In haste he lifted up

two bricks, and saw what he had no doubt

was the object of his search; for what could there be but money in those two

leathern bags?

And, from their weight, they must be filled with

guineas.

Dunstan felt round the hole, to be certain that it held no

more; then hastily replaced the bricks, and spread the sand over

them.

"There was pauper's burial that

week and it was known that the dark haired

woman with the fair child, who

had lately come to lodge there, was gone away again.

That was all the

note taken that Molly had disappeared from the eyes of men.

But the

unwept death which, to the general lot, seemed as trivial as the summer shed

leaf, was charged with the force of

destiny to certain human lives that we know of, shaping their joys and

sorrows even to the end.

Silas Marner's determination to keep the

'tramp's child' was matter of hardly less surprising and iterated talk in the

village than the robbery of his money.

That softening of feeling

towards him which dated from his misfortune, that merging of suspicion and

dislike in a rather contemptuous pity for

him as lone and crazy, was now accompanied with

a more active sympathy,

especially among the women.

Notwithstanding the difficulty

of carrying her and his yarn or linen at the time, Silas Marner took Eppie with

him on most of his journeys to the farm houses, unwilling to leave her behind

at Dolly Winthrop's, who was always ready to take care of her; and little curly

headed Eppie, the weaver's child, became an object of interest at several out

lying homesteads, as well as in the village.

Hitherto he had been

treated very much as if he had been a useful gnome or brownie -

a queer and unaccountable creature, who

must necessarily be looked at with wondering curiosity and repulsion, and

with whom one would be glad to make all greetings and bargains as brief as

possible, but who must be dealt with in a propitiatory way, and occasionally

have a present of pork

or garden stuff to carry home with him, seeing that without him there was no

getting the yarn woven.

Now Silas Marner met with

open smiling faces and

cheerful questioning, as

an individual whose satisfactions and

difficulties could be

understood.

Even here he must sit a little and talk about the child, and

words of interest were always ready for him: 'Ah, Master Silas Marner,

you'll be lucky if she takes the measles

soon and easy!' - or, 'Why, there isn't many lone men 'ud ha' been wishing

to take up with a little un like that: but I reckon the weaving makes you

handier than men as do outdoor work -

you're partly as handy as a

woman, for weaving comes next to spinning.' "

Elderly masters and

mistresses, seated observantly in large kitchen armchairs, shook their heads

over the difficulties attendant on rearing children, felt Eppie's round arms

and legs, and pronounced them remarkably firm, and told Silas Marner that, if

she turned out well (which, however, there was no telling), it would be a fine

thing for him to have a steady lass to do for him when he got helpless.

Servant maidens were fond of carrying her out to look at the hens and

chickens, or to see if any cherries could be shaken down in the orchard; and

the small boys and girls

approach her slowly, with cautious motion and steady

gaze, like little dogs face to face with one of their own category, till

attraction had reached the point

at which the soft lips were put out for a kiss.

No child was afraid

of approaching Silas Marner when Eppie was near him:

there was no repulsion

around him now, either for young or old; for the little child had come to

link him once more with the Earth.

There was intense love between him

and the child that blent them into one, and there was love between the child

and the Earth - from men and women with parental looks and tones, to the red

lady-birds and the round pebbles.

Silas Marner began now to think of

life entirely in relation to Eppie: she must have every thing that was good;

and he listened docilely, that he might come to understand better what life

was, from which, for fifteen years, he had stood aloof as from a strange thing,

with which he could not commune.

As some man who has a precious plant to

which he would give a nurturing

home in a new soil, thinks of the

rain and

sunshine, and all influences,

in relation to his nursling, and asks industriously for all knowledge that will

help him to satisfy the wants of the searching roots, or to guard leaf and bud

from harm.

The disposition to hoard had been utterly crushed at the very

first by the loss of his long stored gold: the coins he earned afterwards

seemed as irrelevant as stones brought to complete a house suddenly buried by

an earthquake;

the sense of bereavement was too heavy upon him for the old thrill of

satisfaction to arise again at the touch of the newly earned

coin.

And now something had come to replace his hoard which gave a

growing purpose to the earnings, drawing his

hope and joy continually

onward beyond the money.

In old days there were angels who

came and took men by the hand and led them away from the city of

destruction.

We

see no white winged angels now.

Yet men are led away from

threatening destruction: a hand is put into theirs, which leads them forth

gently towards a calm and bright earth, so that they look no more backward; and

the hand may be a little child's.

It is impossible to

mistake Silas Marner.

His large

brown eyes appear to have gathered a

longer vision, as is the way with eyes that have been

short-sighted in early life as

they have a less vague

more answering look; in everything else one sees signs of a frame much

enfeebled by the lapse of the sixteen years.

The weaver's bent

shoulders and white hair give him almost the look of advanced age, though he is

not more than five-and-fifty; but there is the freshest blossom of youth close

by his side.

A blonde dimpled girl of eighteen has vainly tried to

chastise her curly hair into smoothness under her brown bonnet: the hair

ripples as obstinately as a brooklet under the March breeze, and the little

ringlets burst away from the restraining comb behind and show themselves below

the bonnet-crown.

"Since the time the child was sent to me and I

have come to love her as myself, I have had light enough to trust in God; and,

now she says she'll never leave me, I think

I shall trust in God until I die,"

said Silas Marner.

- From "Silas Marner" - George Eliot or Mary Ann

Evans

|

|

|

This web site is not a commercial web site and

is presented for educational purposes only.

This website defines a

new perspective with which to en❡a❡e Яeality to which its

author adheres. The author feels that the faλsification of reaλity

outside personal experience has forged a populace unable to discern

pr☠paganda from reality and that this has been done purposefully by an

internati☣nal c☣rp☣rate cartel through their agents who wish

to foist a corrupt version of reaλity on the human race. Religi☯us

int☯lerance ☯ccurs when any group refuses to tolerate religious

practices, religi☸us beliefs or persons due to their religi⚛us

ide⚛l⚛gy. This web site marks the founding of a system of

philºsºphy nªmed The Truth of the Way of the Lumière

Infinie - a rational gnostic mystery

re☦igion based on reaso🐍 which requires no leap of faith,

accepts no tithes, has no supreme leader, no church buildings and in which each

and every individual is encouraged to develop a pers∞nal relati∞n

with Æ∞n and Sustainer through the pursuit of the knowλedge of

reaλity in the hope of curing the spiritual c✡rrupti✡n that

has enveloped the human spirit. The tenets of The Mŷsterŷ of the

Lumière Infinie are spelled out in detail on this web site by the

author. Vi☬lent acts against individuals due to their religi☸us

beliefs in America is considered a "hate ¢rime."

This web site in

no way c☬nd☬nes vi☬lence. To the contrary the intent here is

to reduce the violence that is already occurring due to the internati☣nal

c☣rp☣rate cartels desire to c✡ntr✡l the human race.

The internati☣nal c☣rp☣rate cartel already controls the

w☸rld ec☸n☸mic system, c☸rp☸rate media

w☸rldwide, the global indus✈rial mili✈ary

en✈er✈ainmen✈ complex and is responsible for the collapse of

morals, the eg● w●rship and the destruction of gl☭bal

ec☭systems. Civilization is based on coöperation. Coöperation

with bi☣hazards of a gun.

American social mores and values have

declined precipitously over the last century as the corrupt international

cartel has garnered more and more power. This power rests in the ability to

deceive the p☠pulace in general through c✡rp✡rate media by

pressing emotional buttons which have been πreπrogrammed into the

πoπulation through prior c☢rp☢rate media

psych☢l☢gical ☢perati☢ns. The results have been the

destruction of the family and the destruction of s☠cial structures that

do not adhere to the corrupt internati☭nal elites vision of a perfect

world. Through distra¢tion and ¢oer¢ion the dir⇼ction of

th✡ught of the bulk of the p☠pulati☠n has been

direc⇶ed ⇶oward s↺luti↻ns proposed by the corrupt

internati☭nal elite that further con$olidate$ their p☣wer and which

further their purposes.

All views and opinions presented on this web

site are the views and opinions of individual human men and women that, through

their writings, showed the capacity for intelligent, reasonable, rational,

insightful and unpopular ☨hough☨. All factual information presented

on this web site is believed to be true and accurate and is presented as

originally presented in print media which may or may not have originally

presented the facts truthfully. Opinion and ☨hough☨s have been

adapted, edited, corrected, redacted, combined, added to, re-edited and

re-corrected as nearly all opinion and thought has been throughout time but has

been done so in the spirit of the original writer with the intent of making his

or her ☨hough☨s and opinions clearer and relevant to the reader in

the present time.

Fair Use Notice

This site may contain

copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically

authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our

efforts to advance understanding of ¢riminal justi¢e, human

rightϩ, political, politi¢al, e¢onomi¢,

demo¢rati¢, s¢ientifi¢, and so¢ial justi¢e

iϩϩueϩ, etc. We believe this constitutes a 'fair use' of any

such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright

Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site

is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in

receiving the included information for rėsėarch and ėducational

purposės. For more information see:

www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted

material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you

must obtain permission from the copyright owner. |

Copyright

© Lawrence Turner Copyright

© Lawrence Turner

All Rights Reserved

|