|

The science of

human nature, may be treated after two different ways each of which may

contribute to the entertainment and

reformation of mankind.

The one

considers man chiefly as born for action;

pursuing one object, and avoiding

another, according to the value

which these objects appear to possess, and

according to the light in

which they present themselves.

As virtue is allowed to be the most

valuable, this species of

philosophers paint her in the most amiable colors; borrowing all helps from

poetry and eloquence, and

treating their subject in an easy and obvious manner, and such as is

best fitted to please the

imagination, and engage

the affections.

They select the most

striking observations and

instances from common life;

place opposite characters in a

proper contrast; and alluring us into

the paths of virtue by the views of

glory and happiness, direct our

steps in these paths by the soundest precepts and

most illustrious examples.

They

make us feel the difference between

vice and

virtue; they excite and

regulate sentiments; they bend hearts to the

love of virtue and

true honor.

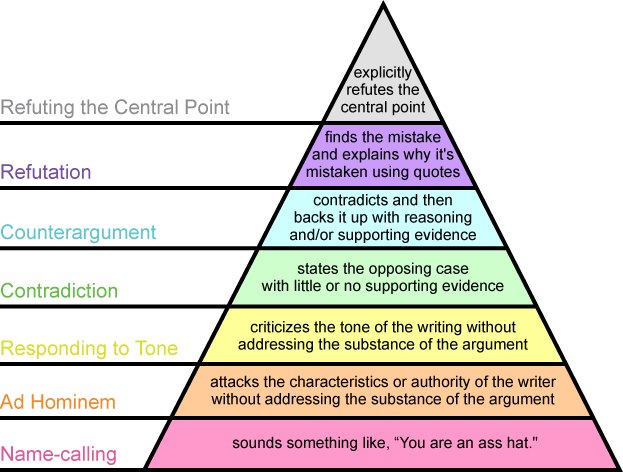

The other philosophers consider

man a reasonable rather than an

active being, endeavor to form

his understanding more than cultivate his manners.

It is easy for a rational

philosopher to commit a mistake and

one mistake is the

necessary parent of another unto the seventh generation.

Speculations appear abstract and

unintelligible to common readers.

Easy obvious philosophy will

be preferred over the

accurately abstruse.

It enters more into common life;

molds the heart and

affections; and, by touching

those principles which actuate men, reforms their

conduct, and brings them

nearer to that model of

perfection which it describes.

This also must be confessed,

durable fame has been acquired by

the easy philosophy; abstract

reasoners appear hitherto to have enjoyed only a momentary reputation, from

the caprice or ignorance of their

own age.

A philosopher, who purposes only

to represent common sense

in beautiful engaging colors,

if by accident he falls into error, sees

his error, returns to the narrow path,

renews

his appeal to common sense

and the natural sentiments of the

mind securing himself from any dangerous

illusions.

Accurate and just reasoning is the only remedy, fitted

for all dispositions.

It alone is

able to subvert abstruse

philosophy and metaphysical

jargon, which being mixed up with

popular superstition,

renders it in a manner impenetrable to careless

thinkers, and gives it the air of science.

After deliberate inquiry rejecting the most uncertain part of man's

purported knowledge, there are many positive advantages, which result from an

accurate scrutiny into the powers and faculties of human nature.

In

operations of the mind whenever

thoughts become

the object of reflection

they appear obscure and ill-defined;

the mind's eye cannot readily

and easily discriminate and distinguish fuzzy abstract lines and

boundaries.

The objects are too fine

to remain long in the same aspect or situation; and must be

apperceived in an instant,

by a superior

penetration, derived from natural

reflection, and improved by habit

and study.

It becomes, therefore,

no inconsiderable part of science

barely to know the different operations of the mind,

to separate them from each other

to class them under their proper heads, and

to correct all that seeming

disorder when made the object of reflection and inquiry.

Everyone will readily allow that there is considerable

difference between the perceptions of the

mind, when a man feels the pain of excessive

heat, or the pleasure of moderate

warmth, and when he afterwards recalls to his memory this

sensation, or anticipates it by his

imagination.

These faculties may

mimic or copy the

perceptions of the senses; but they

never can entirely reach the force and

vivacity of the original sentiment.

When they operate with

greatest vigor they represent their object in so

lively a manner that we could

almost say we feel

or see it or

hear it resonate.

All

the colors of poetry, however splendid,

can never paint natural objects in such a manner

as to make the description be taken for a real

landscape.

The most lively

thought is still inferior to the dullest sensation.

We may

observe the same to run through

all perceptions of the

mind.

A man actuated by

anger reacts differently than an angry man.

When we reflect

on past sentiments and affections,

thought is a unfaithful mirror

for the real disorders and agitations of the

passion.

It requires no discernment to

mark the distinction

between them.

The thought of man not only

escapes all human power and authority

but is not even restrained

within the limits of nature and reality.

To form monsters, and join

incongruous shapes and appearances,

costs the imagination no more trouble than to

conceive natural and familiar

objects.

Heat shock proteins are a

family of proteins produced by cells

in response to exposure to

stressful conditions.

First described in relation to heat shock,

they are expressed during stress including exposure to cold, UV light, wound

healing and tissue remodeling.

Heat shock proteins can function as

molecular chaperones, which have been shown to facilitate protein folding,

prevent protein aggregation, and target improperly folded proteins to

degradative pathways.

They are classified into subfamilies according to

their molecular weight.

Under normal physiological conditions, stress

proteins are low.

In response to cellular stress, protein expressions

dramatically increase.

Stress proteins have been found to participate in

a number of cellular processes that occur during and after

exposure to oxidative stress.

|

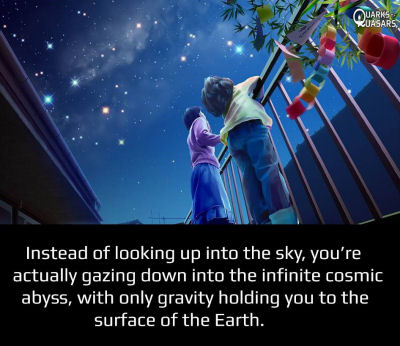

While

the body is confined to the Earth,

along which it creeps with

difficulty; thought can in an

instant transport us into distant regions of reality; or

even beyond reality, into

unbounded chaos,

where natural law no longer

exists.

Though thought appears

to possess unbounded liberty

we find upon nearer

examination it is really confined within very narrow limits.

All

this creative power of the mind

amounts to no more than the faculty

of compounding the materials afforded us by the senses and experience.

All ideas, especially

abstract ones, are

naturally faint and

obscure: the mind has but

a slender hold of them: they are apt to be confounded with other

resembling ideas; we are

apt to imagine a

determinate idea annexed to it.

Bringing ideas into a clear

light removes dispute concerning their

nature!

The principle of connection

within imagination introduces

a logical certainty to the degree of methodical regularity within the dialectic

of memory.

In serious thinking this is so observable that any

particular thought, which breaks in upon the

regular tract or

chain of ideas, is

invariably examined.

Even in our wildest and

most wandering reveries, nay in our very

dreams, we shall find,

if we reflect,

the imagination ran not

altogether wild as there is a connection upheld among the

different ideas, which succeed each other.

Were the loosest and freest conversation to be transcribed, there would

immediately be observed something which connected it in all its transitions.

Or where this is wanting, the individual who broke the thread of

discourse might still inform you, that there had revolved in his mind a

succession of thought, which had gradually led him from the subject of

conversation.

It is found simple ideas are

comprehended in compound ones

bound together by some universal

principle which has an equal

influence on all mankind.

All the objects of human reason or

inquiry may naturally be divided into two kinds; relations of ideas or

relational knowledge and

matters of fact.

Relations of ideas are

geometrically calculable; every

affirmation, either intuitively or

demonstratively certain, must

be provable to become fact.

That the square of the hypothenuse

is equal to the square of the two sides, is

a statement which expresses a

relation between these figures.

Statements of this category are

discovered by the mere operation of thought.

Though there never was

a circle or triangle in nature,

truths demonstrated by

Euclid retain their material certainty through factual evidence.

Matters of fact are accepted

rather than ascertained.

The negation of every

matter of fact is a possiblity, conceived by the mind with the same

facility and distinctness as if it was conformable to reality.

It may be

a subject worthy of curiosity, to

enquire what is the nature of

that evidence which assures us of any real existence and matter of fact,

beyond the present testimony of our senses,

or the records of our memory.

Such enquiries may even prove

useful, by exciting

curiosity but halting implicit faith and security,

the bane of all reasoning and free

enquiry.

In reality, all

arguments from experience are founded

on the similarity which we discover among natural objects, and by which

we are induced to expect effects

similar to those which we have found to follow from such objects.

None but a fool will ever pretend

to dispute the authority of

experience.

It is only after a long

course of uniform experiments in any category, that we attain a firm

reliance and security with regard to a

particular event.

A

long course of uniform experiments shows us a number of uniform effects.

All inferences from

experience suppose that the future

will resemble the past.

If there be suspicion the course of nature may

change, and the past may

be no rule in the future, all

experience becomes useless with no ability

to infer.

All

inferences from experience are effects of expectations, not of

reasoning.

Expectation, then, is

the great guide of human life.

It is that principle

alone which renders experience useful; allowing us to

expect in the future a similar

course of events with those of the past.

Without the influence of

expectation, we should be entirely ignorant of every matter of fact beyond

what is immediately here in the present.

There would be an end at once of all

action.

Some facts must be

present in memory to proceed in drawing a conclusion.

A man finding in a desert country the

remains of pompous buildings would conclude

the country had been cultivated by

civilized inhabitants; but did nothing of this nature occur to him, he

could never form such an

inference.

Taught the

events of former ages from history

we must peruse the original

manuscript carrying inferences from one testimony to another, till we

arrive at the eyewitness' and

spectators of these distant events.

Proceeding upon some fact present to the

memory our reasoning

becomes merely hypothetical; even though

links might be connected with

each other, the

whole chain of inferences would have

nothing to support it.

If I ask why you believe any

particular matter of fact, which you relate, you must tell me some reason;

and this reason will be some other

matter of fact.

As you cannot proceed after this manner, ad

infinitum, you must terminate in some matter of fact; or must allow that

your belief is without

foundation.

All belief

of matter of fact is derived from an object present to the memory and

a perceived connection between

that and another object.

Having found two object - flame and heat -

always connected; if flame or snow be presented anew to the

senses, the mind expects heat or

cold.

This

belief is the necessary result of placing the mind in such circumstances.

It is an operation of the

soul as unavoidable as to

feel gratitude when we receive benefits or

hatred when we meet with

injuries.

All these operations are of natural instincts, which no

reasoning or process of thinking or understanding is able either to produce or

to prevent.

The great

advantage of the mathematical sciences is ideas are always determinate, the

smallest distinction between them is perceptible.

An oval is never

mistaken for a

circle, nor an hyperbola for an

ellipse.

Equilateral

triangles, presented to senses and

apperceived, are

distinguished by boundaries much more exact than

vice and virtue,

right and wrong.

Operations of the understanding

escape us upon the reflection

of memory.

Power to recall the

original object depends upon the

contemplation of

it.

Ambiguity is introduced into reasoning:

similar objects are

readily taken to be the same: and the

conclusion becomes at last very wide of the premises.

If the mind

retains the ideas of geometry determinately, it must carry on a

much longer and more intricate chain

of reasoning and compare ideas much wider of

each other in order to reach the abstruse

truths of morality.

Trace the

principles of reason through a few steps to

acknowledge

ignorance.

The chief

obstacle, therefore, to our improvement in the philosophical or

metaphysical sciences

is the obscurity of ideas, and

ambiguity of terms.

The principal difficulty in the

mathematics is the length of inferences and

compass of thought,

requisite to the forming of

any conclusion.

Our progress in physics is

retarded by the want of proper experiments and phenomena, overlooked even

by the most diligent and prudent

inquiry.

The

science of human nature requires superior care to be surmounted.

All ideas are nothing but copies of

impressions; it is impossible

to think of anything not antecedently noted by either our external or internal

senses.

Complex

ideas, may, perhaps, be well known by definition, which is nothing but

an enumeration of those parts or

simple ideas, that compose them.

When we have pushed up definitions

to the most simple ideas, and

find still more ambiguity

and obscurity; what resource are

we then possessed of?

By what technique can we

throw light upon these

indeterminate ideas, and

render them altogether

precise and determinate to our intellectual view?

It might

reasonably be expected in

questions disputed with great eagerness that

the meaning of all the terms should

have been agreed already.

How easy it appears to give exact

definitions to the terms employed in reasoning,

upon further scrutiny we shall draw a quite

opposite conclusion.

From this circumstance alone we may presume

that there is some ambiguity

in expression and the

disputants affix

different ideas to the words employed.

The faculties of the mind are naturally

alike in every individual; if

men define terms they no long form different opinions of the same subject.

If men attempt

discussion of questions entirely beyond the reach of human capacity

they may long beat the air in their fruitless

contests.

Intelligible definitions would

immediately put an end to the controversy.

As rational philosophers

tend to engage in a labyrinth of

obscurity sensible readers

turn a deaf ear expecting neither instruction

or entertainment.

A

novel argument may serve to renew

discusion of the controversy.

Synchronicity arises from

the uniformity observable in

the operations of nature, where similar

objects are constantly

connected together by inference.

Human nature remains forever and

always still the same, in its principles

and operations; the same

motives always produce the same actions.

Ambition,

avarice,

narcissism,

vanity,

friendship, generosity, public

spirit: this passion, from the

beginning, the source of all the

actions and enterprises.

Would you know the

sentiments and inclinations of the Greeks and

Romans?

Study well the

temper and actions of the French

and English.

Mankind are so much the same, in all times

and places, that history informs us of

nothing new or strange in this particular.

Watching men in all varieties of

circumstances and situations, and become acquainted with the regular springs of human action

and behavior.

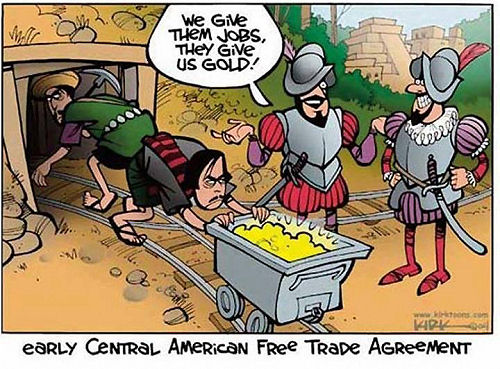

Records of

war, faction and

revolution are

collections of social

experiments.

The social

engineer fixes the principles

of his science through experiments.

To explode any forgery in history, we

cannot make use of a more convincing argument, than to prove, that the actions

ascribed to any individual are directly contrary to the

course of nature, and

that human motives, in such circumstances, induced the

storyteller to

inaccurately report matters

of fact.

The principles of

human nature informs us of nothing new or strange as that

uniformity in every particular,

is found throughout nature.

Universal principles of human

nature furnish material from

observation to become acquainted

with the regular springs of human behavior.

We learn the great force of

education which molds the human

mind from its infancy and forms it

into a fixed and established character.

Even the characters, which

are peculiar to each individual, have a uniformity of character

in the different ages of human

life.

The mutual dependence of men is so great in all societies no

human action is entirely complete in itself, or is performed without reference

to the actions of others, requisite to make it answer fully the

intention of the agent acting.

The poorest craftsman, who

labors alone, expects at least the protection of the magistrate, to ensure him

the enjoyment of the fruits of

his labor.

In these conclusions they take their measures from past

experience; and firmly believe that men are to continue in operations as they

always have.

Experimental inference concerning the actions of others

enters so much into life that no man, while

awake, is ever a moment

without employing it.

Mankind has agreed in theory

on liberty as well as on that of connection.

When we consider how

aptly natural and moral evidence

links together we shall allow they are of the same nature, derived from the

same principles.

When any opinion leads to

absurdities, it is

certainly false; but it is not certain that an opinion is false, because

it seems of dangerous

consequence.

Liberty is the ability to act or

not act consistent with morality.

The mind of man, formed by

nature, displaying certain

characteristics and having dispositions immediately feels the sentiment of

approbation or

blame.

These distinctions are found in

the natural sentiments of the human mind and will not be altered by any

philosophical theory or speculation.

The origin of the

passions of man will acquire authority if we find the same theory is

requisite in explaining the same phenomena in all other animals.

Animals as well as men learn many

things from experience.

Both infer the same events will always

follow from the same causes.

By this principle they become

acquainted with the properties of matter.

The ignorance of youth

contrasts the plainly distinguishable sagacity of the aged, who after long

observation, avoid pain while in pursuit of pleasure.

A horse, accustomed to the

field, becomes acquainted with the proper height which he can leap, and will

never attempt what exceeds his force and

ability.

The horse

infers some matter of fact beyond what immediately strikes his senses and

this inference is altogether founded on past experience.

He expects

from the present situation the same consequences which it has always found in

observation to result from similar objects and conditions.

We possess reasoning in

common with beasts and need not disquisitions of human understanding to

comprehend the objects of our

intellectual faculties

Although

without hesitation mankind acknowledges the doctrine of connection in all ages

they profess the contrary opinion of

separation.

Uncertainty

proceeds from the secret opposition of contrary causes.

It is a

hypothetical pretense refutation is

dangerous to religious

morality.

The general observations treasured up by a course of

experience, give us the clue of human nature, and teach us to unravel all its

intricacies.

Pretexts

and appearances no longer deceive us.

A man is guilty of

unpardonable arrogance who concludes that an argument that has escaped his own

investigation does not really exist.

Nothing appears more surprising to those

who consider human affairs with a philosophical eye, than

the ease

with which the many are governed by a few.

David Hume

|

|

|

This web site is not a commercial web site and

is presented for educational purposes only.

This website defines a

new perspective with which to en❡a❡e Яeality to which its author adheres. The

author feels that the faλsification of reaλity outside personal

experience has forged a populace unable to discern pr☠paganda from

reality and that this has been done purposefully by an internati☣nal

c☣rp☣rate cartel through their agents who wish to foist a corrupt

version of reaλity on the human race. Religi☯us int☯lerance

☯ccurs when any group refuses to tolerate religious practices,

religi☸us beliefs or persons due to their religi⚛us

ide⚛l⚛gy. This web site marks the founding of a system of

philºsºphy nªmed The Truth of the Way of the Lumière

Infinie - a ra☨ional gnos☨ic mys☨ery re☦igion based on

reason which requires no leap of faith, accepts no tithes, has no supreme

leader, no church buildings and in which each and every individual is

encouraged to develop a pers∞nal relati∞n with the Æon

through the pursuit of the knowλedge of reaλity in the hope of curing

the spiritual c✡rrupti✡n that has enveloped the human spirit. The

tenets of The Mŷsterŷ of the Lumière Infinie are spelled out

in detail on this web site by the author. Vi☬lent acts against

individuals due to their religi☸us beliefs in America is considered a

"hate ¢rime."

This web site in no way c☬nd☬nes

vi☬lence. To the contrary the intent here is to reduce the violence that

is already occurring due to the internati☣nal c☣rp☣rate

cartels desire to c✡ntr✡l the human race. The internati☣nal

c☣rp☣rate cartel already controls the w☸rld

ec☸n☸mic system, c☸rp☸rate media w☸rldwide, the

global indus✈rial mili✈ary en✈er✈ainmen✈ complex

and is responsible for the collapse of morals, the eg● w●rship and

the destruction of gl☭bal ec☭systems. Civilization is based on

coöperation. Coöperation with bi☣hazards of a

gun.

American social mores and values have declined precipitously over

the last century as the corrupt international cartel has garnered more and more

power. This power rests in the ability to deceive the p☠pulace in general

through c✡rp✡rate media by pressing emotional buttons which have

been πreπrogrammed into the πoπulation through prior

c☢rp☢rate media psych☢l☢gical ☢perati☢ns.

The results have been the destruction of the family and the destruction of

s☠cial structures that do not adhere to the corrupt internati☭nal

elites vision of a perfect world. Through distra¢tion and

¢oer¢ion the dir⇼ction of th✡ught of the bulk of the

p☠pulati☠n has been direc⇶ed ⇶oward

s↺luti↻ns proposed by the corrupt internati☭nal elite that

further con$olidate$ their p☣wer and which further their purposes.

All views and opinions presented on this web site are the views and

opinions of individual human men and women that, through their writings, showed

the capacity for intelligent, reasonable, rational, insightful and unpopular

☨hough☨. All factual information presented on this web site is

believed to be true and accurate and is presented as originally presented in

print media which may or may not have originally presented the facts

truthfully. Opinion and ☨hough☨s have been adapted, edited,

corrected, redacted, combined, added to, re-edited and re-corrected as nearly

all opinion and ☨hough☨ has been throughout time but has been done

so in the spirit of the original writer with the intent of making his or her

☨hough☨s and opinions clearer and relevant to the reader in the

present time.

Fair Use Notice

This site may contain

copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically

authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our

efforts to advance understanding of ¢riminal justi¢e, human

rightϩ, political, politi¢al, e¢onomi¢,

demo¢rati¢, s¢ientifi¢, and so¢ial justi¢e

iϩϩueϩ, etc. We believe this constitutes a 'fair use' of any

such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright

Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site

is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in

receiving the included information for rėsėarch and ėducational

purposės. For more information see:

www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted

material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you

must obtain permission from the copyright owner. |

Copyright

© Lawrence Turner Copyright

© Lawrence Turner

All Rights Reserved

|