|

From the winter

of 1821 I had what might truly be called an object in life:

to be a Reformer.

My conception of my own

happiness was entirely identified with this object.

The personal

sympathies I wished for were those of

fellows in this

enterprise.

I endeavored

to pick as many flowers as I

could but as a serious permanent

personal satisfaction to rest upon, my whole reliance was placed on

this.

I was accustomed to

the certainty of a happy life which I enjoyed, by placing my happiness in

something durable and distant, in which

progress might be always making, while it could never be exhausted by complete

attainment.

The general improvement and the idea of myself engaged with

others in struggling to promote it, seemed enough to fill up an animated

existence.

The time came when I awakened from

this as from a dream.

It was in

the autumn of 1826.

(1826: First railways begin construction.

Internal Combustion engine patented in US.

Janissary on the rampage,

Auspicious

Incident.)

I was in a

dull state of nerves, such

as everybody is occasionally liable to.

Unsusceptible to enjoyment or pleasurable

excitement.

One of

those moods when what is pleasure at other times, becomes

insipid.

The mood of converts to Methodism smitten

by 'conviction of

sin.'

In this frame of

mind it occurred to me to put the question directly to

myself:

"Suppose your objects in life were realized;

all the changes in institutions and

opinions which you are looking

forward to, could be completely

effected at this very instant: would this be a great joy and happiness to

you?"

And an irrepressible

self-consciousness distinctly answered, "No!"

At this my heart

sank: the foundation on which my life was built

fell down.

All my

happiness was to have been found in the continual pursuit of this end.

Once the end ceased to charm, how could

there be any interest in the means?

I seemed to have nothing left

to live for.

For I now saw, the habit of

analysis has a tendency

to wear away feelings.

When

no other mental habit is

cultivated analysis remains

without natural complements and

correctives.

The

very excellence of analysis is that it tends to weaken and undermine whatever

is the result of false understanding or

prejudice.

It enables us mentally to

separate ideas which have only casually clung together and

no associations could ultimately

resist this dissolving force.

We owe to analysis our clearest

knowledge of the permanent

sequences in nature; the

real connections between things, not dependent on imaginings.

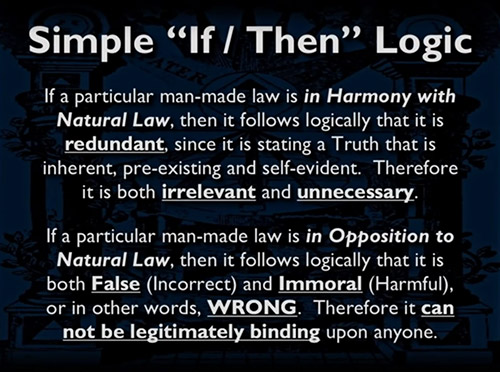

Natural law finds

one thing is inseparable from

another; our ideas of things joined together in

Nature,

cohere more and more closely in our

thoughts.

Analytic habits

strengthen the associations

between causes and effects.

But analytic habits tend to weaken

associations which are a

matter of feeling.

Analytic habits are therefore favorable to

prudence and

clear sightedness.

But

analytic habits are a

perpetual worm at the root

both of the passions and

of the virtues; and

fearfully undermine all desires,

and all pleasures.

These, the

laws of human nature,

had been brought to my present state.

Those whom I admired were of

opinion that companionship

and feelings of

compassion, especially

toward mankind on a large scale as the object of existence, were

the greatest and surest sources of

happiness.

Of the truth of this I was convinced, but

to know that a feeling would make

me happy if I had it, did not

give me the feeling.

My education, I thought, had failed to create

these feelings in sufficient strength to

resist the dissolving

influence of analysis.

The whole course of my intellectual

cultivation had made

precocious and

pre-mature analysis the inveterate habit of

my mind.

The fountains

of vanity and motivation seemed to have

dried up within me, as completely as the

river of benevolence, I

once had.

Thus neither selfish nor

unselfish pleasures were

pleasures to me.

There seemed no

power in nature sufficient

to reform my character anew.

My mind, now irretrievably

analytic, needed fresh associations of

pleasure combined with objects of

human desire to relish living again.

I asked myself if I was bound

to life must be passed in this manner?

I did not think I could possibly

bear it beyond a year.

In all

probability my case was by no

means so peculiar as I fancied.

A vivid conception of the scene came over

me, and I was moved to tears.

From this moment my burden grew

lighter.

The oppression of the

thought that all feeling was dead within me, was gone.

I was no longer hopeless.

Relieved from my present sense

of irremediable wretchedness, I gradually found that the

ordinary incidents of life

could again give me some pleasure.

I found enjoyment in

sunshine and

sky; books; conversation; public

affairs.

There was excitement in

exerting my opinions for the

public good.

Thus the cloud gradually drew

off.

I never again was as miserable as I had been.

The

experiences of this period led me to adopt a theory of life, unlike that on

which I had before acted having much in common with what at that time I

certainly had never heard of, the automaton theory of Thomas

Carlyle.

I now

understood happiness was attained by not making it the direct

end.

Only those with minds

fixed on some object other than their own happiness;

on the happiness of

others, on the

improvement of mankind, even on some art or pursuit, followed not

as a means, but as itself an ideal end, are happy.

Aiming thus at something else, they find

happiness by the Way.

Ask yourself whether you are

happy, and you cease to be so.

The only chance for happiness is

finding it within the purpose of

living.

In fortunate circumstances you will

inhale happiness with the air you

breathe never putting

it to flight with fatal questioning.

This theory now became the

basis of my philosophy of life.

I still hold it as the best theory for

those who have but a moderate degree of sensibility and of capacity for

enjoyment - the great majority of mankind.

I ceased to attach

exclusive importance on ordering

outward circumstances.

I saw passive susceptibilities needed to be

cultivated as well as the active capacities and both required to be nourished

and enriched as well as guided.

Maintenance of balance among the

faculties, seemed of primary importance.

1829 Edinburgh Review published Thomas Carlyle's "Signs of

the Times".

In "Signs of the Times", Carlyle warns the

Industrial Revolution is turning people into mechanical automatons devoid of

individuality and spirituality.

The division of society and the poverty

of the majority began to dominate the minds of the most intelligent and

imaginative people outside politics following the 1832 Reform Act.

The

"Condition of England Question" was a phrase coined by Thomas Carlyle in 1839

to chronicle the conditions

of the English working-class during the Industrial Revolution.

There

was a growing sense of anger at the culture of amateurism in official

government circles which produced this misery.

Structural changes in

the economy led many to question whether the country had taken a wrong turning.

Would manufacturing towns ever be loyal?

Was poverty eating up

capital?

Was it safe to depend upon imports for food and raw materials?

Could the fleet keep the seas open?

Should government encourage

emigration and require those who remained behind to support themselves by spade

husbandry?

These were the 'Condition of England' questions".

|

I now began to find

meaning in the importance of

poetry and

art.

The only

imaginative arts I had taken

pleasure in was music.

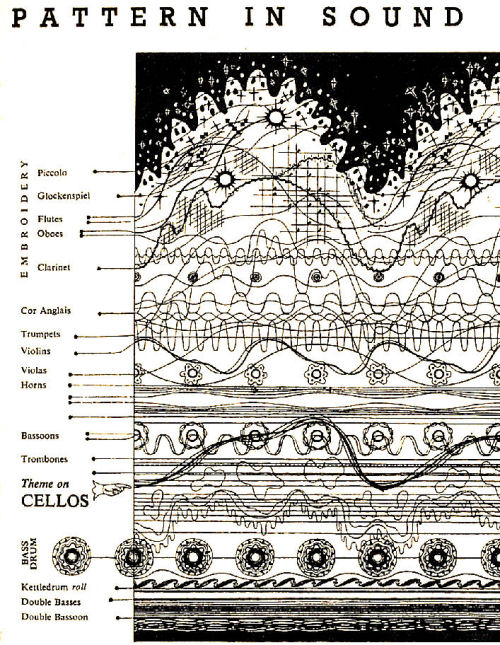

The best effect consists in winding up to a high

pitch feelings of an elevated category to which this excitement gives a glow

and a fervor, which, though transitory at its utmost height, is precious for

sustaining them at other times.

This effect of music I had often

experienced; but like all my pleasurable susceptibilities it was suspended

during the gloomy period.

I had sought relief again and again from this quarter, but found none.

After the tide had turned, and I was in process of recovery, I had been

helped forward by music, but in a much less elevated manner.

I became

acquainted with Weber's Oberon, and the

extreme pleasure showed me

a source of pleasure to which I

was as susceptible as ever.

Happiness was impaired by the thought

the pleasure of music fades with

familiarity requiring revival through intermittence

or continual novelty.

I

was seriously tormented by the exhaustibility of

musical combinations.

This

source of anxiety may,

perhaps, be thought to resemble that of the

philosophers of

Laputa, who feared lest the sun

should be burnt out.

In the power of rural beauty, there was a

foundation laid for pleasure in

Wordsworth's poetry as his scenery lies mostly mountains,

which, owing to my early Pyrenean excursion, were my

ideal of natural beauty.

What made

Wordsworth's poems a medicine for my state of

mind, was that they

expressed, not mere outward

beauty, but states of feeling,

of thought colored by feeling;

the excitement of the

rememberance of natural beauty.

They seemed to be the very culture

of the feelings, which I was in quest

of.

In them I seemed to draw from a source of inward joy,

of sympathetic and imaginative

pleasure, which could be shared in by

all human beings; which had no

connection with struggle or imperfection, but would be made richer by every

improvement in the physical or social condition of mankind.

From them I seemed to

learn what would be the

perennial sources of happiness, when all the greater evils of life shall

have been removed.

And I

felt myself at once better and happier as I came under their influence.

There have certainly been greater poets than Wordsworth; poetry of

deeper and loftier feeling could not have done for me at that time what his

did.

I needed to

feel there was permanent happiness in tranquil contemplation.

Wordsworth taught me this, not only without turning away from, but with

a greatly increased interest in the common feelings and

destiny of people.

The

delight which these poems gave

me, proved that with culture of this sort, there was nothing to dread from the

most confirmed habit of analysis.

The aim, therefore, of

patriots, was to set limits to the power which the ruler should exercise over

the community; and this limitation was what they meant by liberty;

protection from the tyranny of political

rulers.

It was attempted in two ways.

First, by obtaining a

recognition political liberties or

rights, which it was to be regarded as

a breach of duty in the ruler

to infringe, and which, if he did infringe, specific résistance, or

general rebellion, was held to be justifiable.

A second, and generally

a later expedient, was

the establishment of constitutional

checks; by which the consent of the community, or of

a body of some sort supposed to

represent community interests, was made a necessary condition to some

important acts of the governing power.

A time, however, came in the

progress of human affairs, when men ceased to think it

a necessity of nature

that their governors should be an independent

power, opposed in interest to

themselves.

It appeared to them much better that the various

magistrates of the State should be their tenants or

delegates, revocable at their

pleasure.

In that way alone, it seemed, could they have complete

security that the powers of government

would never be abused to their disadvantage.

The clearer perception

and livelier impression of truth produced by its

collision with error.

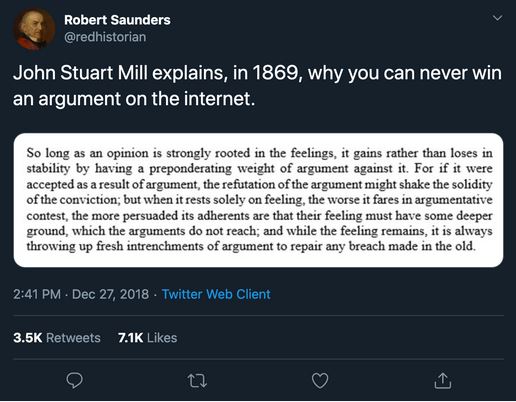

If any

opinion be compelled to

silence that opinion must be true.

To deny this is to

assume our own

infallibility. |

|

|

This web site is not a commercial web site and

is presented for educational purposes only.

This website defines a

new perspective with which to en❡a❡e Яeality to which its author adheres. The

author feels that the faλsification of reaλity outside personal

experience has forged a populace unable to discern pr☠paganda from

reality and that this has been done purposefully by an internati☣nal

c☣rp☣rate cartel through their agents who wish to foist a corrupt

version of reaλity on the human race. Religi☯us int☯lerance

☯ccurs when any group refuses to tolerate religious practices,

religi☸us beliefs or persons due to their religi⚛us

ide⚛l⚛gy. This web site marks the founding of a system of

philºsºphy nªmed The Truth of the Way of the Lumière

Infinie - a ra☨ional gnos☨ic mys☨ery re☦igion based on

reason which requires no leap of faith, accepts no tithes, has no supreme

leader, no church buildings and in which each and every individual is

encouraged to develop a pers∞nal relati∞n with Æ∞n

through the pursuit of the knowλedge of reaλity in the hope of curing

the spiritual c✡rrupti✡n that has enveloped the human spirit. The

tenets of The Mŷsterŷ of the Lumière Infinie are spelled out

in detail on this web site by the author. Vi☬lent acts against

individuals due to their religi☸us beliefs in America is considered a

"hate ¢rime."

This web site in no way c☬nd☬nes

vi☬lence. To the contrary the intent here is to reduce the violence that

is already occurring due to the internati☣nal c☣rp☣rate

cartels desire to c✡ntr✡l the human race. The internati☣nal

c☣rp☣rate cartel already controls the w☸rld

ec☸n☸mic system, c☸rp☸rate media w☸rldwide, the

global indus✈rial mili✈ary en✈er✈ainmen✈ complex

and is responsible for the collapse of morals, the eg● w●rship and

the destruction of gl☭bal ec☭systems. Civilization is based on

coöperation. Coöperation with bi☣hazards of a

gun.

American social mores and values have declined precipitously over

the last century as the corrupt international cartel has garnered more and more

power. This power rests in the ability to deceive the p☠pulace in general

through c✡rp✡rate media by pressing emotional buttons which have

been πreπrogrammed into the πoπulation through prior

c☢rp☢rate media psych☢l☢gical ☢perati☢ns.

The results have been the destruction of the family and the destruction of

s☠cial structures that do not adhere to the corrupt internati☭nal

elites vision of a perfect world. Through distra¢tion and

¢oer¢ion the dir⇼ction of th✡ught of the bulk of the

p☠pulati☠n has been direc⇶ed ⇶oward

s↺luti↻ns proposed by the corrupt internati☭nal elite that

further con$olidate$ their p☣wer and which further their purposes.

All views and opinions presented on this web site are the views and

opinions of individual human men and women that, through their writings, showed

the capacity for intelligent, reasonable, rational, insightful and unpopular

☨hough☨. All factual information presented on this web site is

believed to be true and accurate and is presented as originally presented in

print media which may or may not have originally presented the facts

truthfully. Opinion and ☨hough☨s have been adapted, edited,

corrected, redacted, combined, added to, re-edited and re-corrected as nearly

all opinion and ☨hough☨ has been throughout time but has been done

so in the spirit of the original writer with the intent of making his or her

☨hough☨s and opinions clearer and relevant to the reader in the

present time.

Fair Use Notice

This site may contain

copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically

authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our

efforts to advance understanding of ¢riminal justi¢e, human

rightϩ, political, politi¢al, e¢onomi¢,

demo¢rati¢, s¢ientifi¢, and so¢ial justi¢e

iϩϩueϩ, etc. We believe this constitutes a 'fair use' of any

such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright

Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site

is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in

receiving the included information for rėsėarch and ėducational

purposės. For more information see:

www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted

material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you

must obtain permission from the copyright owner. |

Copyright

© Lawrence Turner Copyright

© Lawrence Turner

All Rights Reserved

|