|

Descartes is often regarded as the first thinker

to

emphasize the use of reason to develop the natural sciences.

1637 Rene Decartes

publishes Discours de la méthode.

A method for discovery of truth consists of

four rules:

Accept

nothing as true unless one has no

doubt.

Divide up each

problem into as many

parts as possible and resolve

each in the manner best suited to the task.

Carry on reflections

beginning with the most simple and proceed

little by little, to knowledge

of the most complex.

Make

enumerations so complete

and reviews so general so one

can be certain of omitting no

active possibility.

"Man is composed of

a twofold nature, a

spiritual and a

bodily.

As regards

the spiritual nature, which they

name the soul, he is called the spiritual, inward,

new man; as

regards the bodily nature, which they name the flesh, he is called the fleshly,

outward, old man." - Martin

Luther

Common sense is, of all things

among men, the most equally

distributed.

Each thinks himself so abundantly provided, even those

difficult to satisfy,

do not usually desire a larger

measure than they already possess.

It is not likely that all are

mistaken the conviction it is rather to be held as testifying

the power of judging aright and

distinguishing truth from

error, properly called common sense or

reason, is

by nature equal in all men.

The diversity of our

opinions does not arise from some being endowed with a larger

share of reason than others, but solely by this,

we conduct our thoughts along

different ways, and do not fix

attention on the same objects.

To be possessed of a vigorous mind

the prime requisite is to

rightly apply it.

He truly

engages in battle who endeavors to surmount all the

difficulties and errors which prevent him from reaching the

knowledge of truth.

I, Rene

Descartes, hold in esteem the studies of the schools.

I was aware that the languages

taught in them are necessary to the understanding of

the writings of the ancients;

that the grace of

narrative stirs the mind;

that the memorable deeds of history elevate it;

and, if read with

discretion, aid in forming

judgement;

the perusal of

excellent books interviews the

noblest men of past ages;

that eloquence has incomparable force and beauty;

that poetry has its

ravishing, its graces and

delights;

that in the mathematics there are

refined discoveries

eminently suited to gratify the inquisitive,

further all the arts and lessen the

labor of man;

that numerous highly useful precepts

and exhortations to

virtue;

that theology

points out the path to heaven;

that philosophy affords the means

of discoursing with an appearance of truth on all matters, and

commands the admiration of the

simple;

that jurisprudence,

medicine, and the other sciences,

secure for their cultivators

honors revealing superstition and

error, that we may be in a

position to determine real

value, and guard against

being deceived.

I, Rene Descartes, am not at all astonished at

the extravagances

attributed to those ancient philosophers whose

own writings we do not possess.

I do not suppose them to

have really been absurd, seeing they were among the ablest

men, but only that these have been falsely represented to us.

I am quite sure that

the most devoted of the

followers of Aristotle would

think themselves happy if they

had the knowledge of nature he

possessed.

I, Rene Descartes,

never accepted anything for

true which I did not clearly know to be such unless

presented so distinctly as to

exclude all doubt.

I divide each of

the difficulties under examination into as many parts as possible, and

as might be necessary for its

adequate solution.

Commencing with objects the

simplest and easiest to know

I ascend step by step to

the knowledge of the more

complex and difficult to

understand.

The

long chains of simple reason led me to

envision that all things are

mutually connected in the same

way through unswayable physical

rules.

There is nothing so far removed to

be beyond understanding.

Nothing so hidden we cannot

discover it, provided only

we abstain from accepting the

false for the true, and always preserve in our thoughts

the order necessary for the deduction of

one truth sequentially from

another.

Each truth

discovered made available the discovery of subsequent ones.

Expediency seemed to dictate that I

should regulate my behavior conformably to

the opinions of those with whom I

should have to live.

In

order to ascertain the real opinions of such, I ought rather to take

cognizance of what they

practiced rather than of what they said.

In

the corruption of our

manners, there are few disposed to

speak exactly as they believe, but also

many are not aware of what it is

they really believe.

Something

believed is different from something known.

When it is not in our power to

determine what is true, we

ought to act according to what is most probable. (Apply Ockham's

Razor)

I, Rene Descartes, endeavor to

conquer myself rather than fortune as

only our own thoughts are in our

power and to conform desire with natural order.

If we

consider all objectives as beyond

our power, we shall no more regret the absence of success when deprived if we

recognize no fault of our own.

It is

my conviction I could not do better than continue

devoting my whole life to the

cultivation of reason; making progress in the

knowledge of truth.

I, Rene Descartes, attentively

examined what I was.

I observed I could envision that I had no

body, and that there was no Earth,

nor any place in which I might

be, but I could not envision that I

was not.

I still was, on the contrary, from the very circumstance

that I thought to doubt the truth

of other things, it most

clearly followed that I remained.

I, Rene Descartes, concluded

I was a substance whose whole essence or

nature consists only in thinking

not dependent on anything

material.

Rene Descartes = Cartesius

I, that is to say, the

mind by which I

am what I

am, is wholly distinct

from the body, and is even

more easily known than the body(?),

and is such, that although the body were not, it would still continue to be all

that it is.

Although I, Rene Descartes,

might think I was dreaming,

that all which I saw or imagined

was false, I could not deny the reality of my

thoughts.

I was disposed straightway to

search for other truths.

I, Rene Descartes, perceived that there was

nothing to these demonstrations

which could assure me of the

existence of an objective actual reality.

For example,

supposing a triangle to be

given, I distinctly perceived that its

three angles were necessarily

equal to two right angles, but I did not on that account

perceive anything which could

assure me that any triangle

existed.

Many are

persuaded there is a difficulty in knowing this truth; in knowing what

their mind really is because they never engage in

abstract

reasoning.

They

consider everything through visualization, a

mode of thinking limited to

real objects; all that is

unimaginable appears to them

unintelligible.

The truth

of this is manifest from the single point the

philosophers accept as a maxim there is

nothing not previously indentified by the

senses.

To comprehend

abstraction they do exactly the same thing as if, in order to

hear sounds or

smell odors,

they strove to avail themselves of

their eyes.

Unless indeed the

sense of sight does not afford us an inferior assurance to those of

smell or

hearing; in place of

which, neither our imagination

nor our senses can give us assurance

of anything unless our understanding intervene.

God is or exists because all that we possess is

derived from God.

It follows that

our ideas or notions, which

to the extent of their clearness

and distinctness are real, and proceed from God, must

to that extent be

true.

We not infrequently have ideas

or notions in which some falsity is contained,

this can only be the case

when we proceed from lack of knowledge.

After

knowledge has rendered us

certain, we can easily understand that the truth of reason

we experience when

awake, ought not in the slightest degree to be

called into question on

account of the illusions of our dreams.

Never be persuaded of the truth of anything unless on the evidence of

reason.

I have observed

laws established by God

are observed in all that exists.

Concatenation of

these laws reveal many

truths more useful and more important than all I had before learned, or

even had expected to learn.

If God were to now compose a universe

and after that did nothing more than lend ordinary concurrence to nature,

and allow nature to act in accordance with the

Laws of Nature, the result,

by necessity, would be as our

reality is.

I, Rene Descartes, endeavored to demonstrate to all until there

could be any room for doubt, and

to prove that even if God had

forged more worlds, there could have been none

in which these laws were not observed.

An opinion commonly received

among theologians:

the action which sustains the

universe is the same with that by which it was originally forged.

God, in the miracle of

Creation, established certain Laws of Nature.

Things

purely material might have become as we observe them at present.

Their

nature is easily envisioned when

beheld coming in this manner gradually into existence,

rather than at once in a

finished perfect state.

I, Rene Descartes,

perceived it to be possible to arrive at

knowledge highly useful in life; so

natural that no one can

imagine himself ignorant of it.

In light of the speculative

philosophy usually taught in the schools, to discover a practical means by

which to know the force and action of fire, water, air, the stars, the

heavens, and the other

elements that surround us.

As distinctly as we know

the various crafts of our artisans,

we might also apply them to render ourselves

the lords and possessors of

nature.

Fruits of the

Earth, the blessings of life,

preserve health.

I

examined what were the first and most ordinary effects that could be deduced

from these causes; and found knowledge of the heavens and

on Earth knowledge of water, air, fire,

minerals, and other things which of all others are the most common and simple,

and hence the easiest to know.

I, Rene Descartes,

deduce germs of truths naturally existing

in our minds.

It is necessary to confess the power of nature is so

ample and these principles so simple and general, that I have hardly observed a

single particular effect which I cannot at once recognize as capable of being

deduced by mankind.

Thereupon, turning over in my mind, the real objects

that had ever been presented to my senses I freely venture to state that I have

never observed any which I could not satisfactorily explain by the

Laws of Nature.

I,

Rene Descartes, am confident there is no one who does not admit

all that is presently known is

nothing in comparison of what

remains to be discovered.

I incite men to strive to proceed farther

by informing the public of all they might

discover, the last beginning

where those before left off connecting

the lives and labors of many

we might collectively

proceed much farther.

If I, Rene Descartes, were to

publish the principles of my

philosophy: to assent to them no more is needed than simply to understand

them.

I foresee that I shall

frequently be turned aside from my grand voyage of discovery on occasion of

the opposition it is sure to

awaken.

By publishing the principles of the

my philosophy I hope to throw open the windows and allow the light of day to

enter.

Rene Descartes

It is likely that Rene Descartes died of

arsenic

poisioning while tutoring

Queen Cristina of Sweden.

Enlightenment comes

from brief insights into the nature of things.

Although such insights

are rare and difficult to sustain they allow

a glimpse of the basis of desire

granting us the ability to control that

desire.

Those who have mastery over desire will walk in

integrity.

Those who possess this knowledge of Self readily come to believe that

any other individual can have the same knowledge about Self as this knowledge

involves nothing which depends on anything outside of Self.

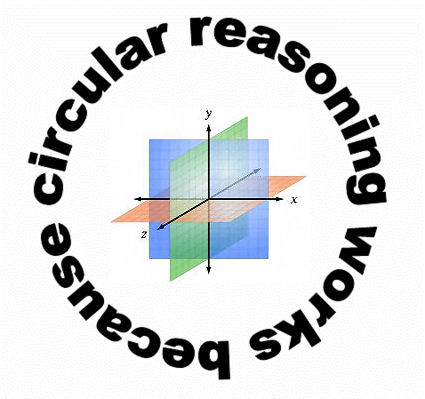

"The Scientific Method relies

for its supra-cultural validity on principles that are

themselves among its own

assumptions.

The

logic of its

justification is circular.

A parallel

would be an aborigine insisting, "Okay, let's settle this question of whether

scientific experiment or

dreaming is the way to true

knowledge once and for all. Let's settle it by entering the

dreamtime and asking ancestors."

The principal

assumptions of objectivity

and determinism at the

foundation of the Scientific

Method are not shared by all traditions of thought.

A

non-objective, non-deterministic, coherent system of thought is possible.

It is more than possible: it is necessary given the impending collapse

of the world of the discrete and separate self that we have wrought.

Necessary in light of the new

scientific revolution of the last hundred years.

Our ways of thinking are not working

anymore." - Charles Eisenstein

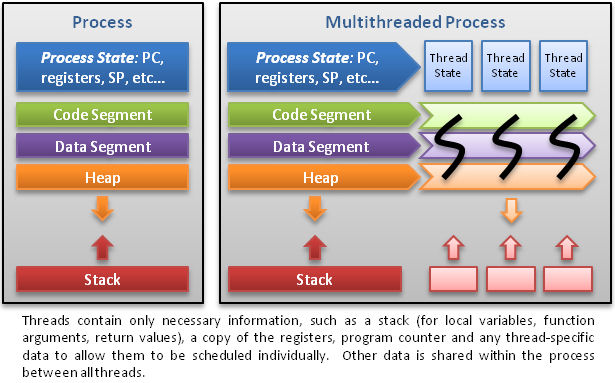

La methodé contained three

appendices: La Dioptrique, Les Météories, and La

Géométrie.

In La Géométrie Descartes

proposed each point on a two dimensional plane can be represented by two

numbers, one giving the point's horizontal location and the other the vertical

location - Cartesian coordinates.

Perpendicular lines (or axes), cross

at a point called the origin, to measure the horizontal (x) and vertical (y)

locations, both positive and negative, thus effectively dividing the plane up

into four quadrants.

Any equation can be represented on the plane by

plotting on it the solution set of the equation.

This can be

extrapolated into three dimensions as seen above. |

|

|

This web site is not a commercial web site and

is presented for educational purposes only.

This website defines a

new perspective with which to en❡a❡e Яeality to which its author adheres. The

author feels that the faλsification of reaλity outside personal

experience has forged a populace unable to discern pr☠paganda from

reality and that this has been done purposefully by an internati☣nal

c☣rp☣rate cartel through their agents who wish to foist a corrupt

version of reaλity on the human race. Religi☯us int☯lerance

☯ccurs when any group refuses to tolerate religious practices,

religi☸us beliefs or persons due to their religi⚛us

ide⚛l⚛gy. This web site marks the founding of a system of

philºsºphy nªmed The Truth of the Way of the Lumière

Infinie - a ra☨ional gnos☨ic mys☨ery re☦igion based on

reason which requires no leap of faith, accepts no tithes, has no supreme

leader, no church buildings and in which each and every individual is

encouraged to develop a pers∞nal relati∞n with the Æon

through the pursuit of the knowλedge of reaλity in the hope of curing

the spiritual c✡rrupti✡n that has enveloped the human spirit. The

tenets of The Mŷsterŷ of the Lumière Infinie are spelled out

in detail on this web site by the author. Vi☬lent acts against

individuals due to their religi☸us beliefs in America is considered a

"hate ¢rime."

This web site in no way c☬nd☬nes

vi☬lence. To the contrary the intent here is to reduce the violence that

is already occurring due to the internati☣nal c☣rp☣rate

cartels desire to c✡ntr✡l the human race. The internati☣nal

c☣rp☣rate cartel already controls the w☸rld

ec☸n☸mic system, c☸rp☸rate media w☸rldwide, the

global indus✈rial mili✈ary en✈er✈ainmen✈ complex

and is responsible for the collapse of morals, the eg● w●rship and

the destruction of gl☭bal ec☭systems. Civilization is based on

coöperation. Coöperation with bi☣hazards of a

gun.

American social mores and values have declined precipitously over

the last century as the corrupt international cartel has garnered more and more

power. This power rests in the ability to deceive the p☠pulace in general

through c✡rp✡rate media by pressing emotional buttons which have

been πreπrogrammed into the πoπulation through prior

c☢rp☢rate media psych☢l☢gical ☢perati☢ns.

The results have been the destruction of the family and the destruction of

s☠cial structures that do not adhere to the corrupt internati☭nal

elites vision of a perfect world. Through distra˘tion and ˘oer˘ion the

dir⇼ction of th✡ught of the bulk of the p☠pulati☠n has been

direc⇶ed ⇶oward s↺luti↻ns proposed by the corrupt internati☭nal elite

that further con$olidate$ their p☣wer and which further their purposes.

All views and opinions presented on this web site are the views and

opinions of individual human men and women that, through their writings, showed

the capacity for intelligent, reasonable, rational, insightful and unpopular

☨hough☨. All factual information presented on this web site is believed to be

true and accurate and is presented as originally presented in print media which

may or may not have originally presented the facts truthfully. Opinion and

☨hough☨s have been adapted, edited, corrected, redacted, combined, added to,

re-edited and re-corrected as nearly all opinion and ☨hough☨ has been

throughout time but has been done so in the spirit of the original writer with

the intent of making his or her ☨hough☨s and opinions clearer and relevant to

the reader in the present time.

Fair Use Notice

This site may contain

copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically

authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our

efforts to advance understanding of ¢riminal justi¢e, human

rightϩ, political, politi¢al, e¢onomi¢,

demo¢rati¢, s¢ientifi¢, and so¢ial justi¢e

iϩϩueϩ, etc. We believe this constitutes a 'fair use' of any

such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright

Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site

is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in

receiving the included information for rėsėarch and ėducational

purposės. For more information see:

www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted

material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you

must obtain permission from the copyright owner. |

Copyright

© Lawrence Turner Copyright

© Lawrence Turner

All Rights Reserved

|